Four-storey limits and the challenge of affordable housing in Ottawa

The City of Ottawa Council decision to limit development on Minor Corridors to 4 stories instead of 6 shows the challenges of balancing societal needs when aspiring to be the best mid-sized city in North America.

These corridors, including Gladstone, Kirkwood, Churchill and Donald Avenues, are the perfect places to create moderate infill density. These streets can support ground floor small businesses and well-designed infill. Many are already home to mid and high-rise apartment buildings, transit and bike lanes.

Fixed costs like planning applications, studies and reports, as well as services for power, sewer, storm water, excavations, basements, elevators and the infrastructure for sprinkler, heating and cooling systems are essentially the same regardless if the building is 4 or 6 stories. This challenge is noted by the Ontario Association of Architects Housing Affordability Report.

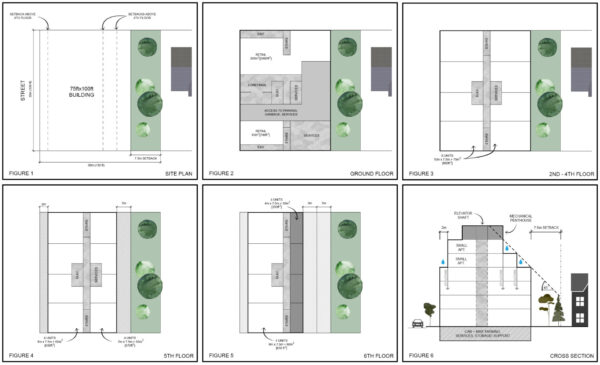

Consider an example site where a 6 storey mixed use residential building with 8 units per floor, ground floor retail or commercial uses, could have 40 good sized homes (8 units per floor from 2-6). If this is limited to four floors, that drops to 24 units. The reduced height means that there are fewer units to spread that cost, making each of the remaining units more expensive.

While it is possible to build four stories in conventional wood framing, the builder’s risk insurance is so high that most developers shy away from this sort of construction. Concrete, steel or mass timber construction are possible but there is too little repetition to make this scale of building financially viable.

The result is that anything built on these Minor Corridors is likely to be expensive housing, furthering the affordability crisis. Anyone developing land on these streets will likely file appeals to rezone their property to increase the height even more than 6 stories help cover the cost of the appeal, delays and planning fights. That further divides communities and the development industry, exacerbating an already strained relationship.

Layered on this is the challenge of zoning. Kirkwood, for example, has 11 different zoning designations along its 1.1km length from Richmond to Carling, comprising everything from detached residential R1 to 66m high-rise residential R5 zoning along with Traditional Mainstreet (TM) and General Mixed-Use zones.

Yet Kirkwood is the exact sort of street we want to encourage gentle, affordable, density. It is anchored at both south and north with shopping that meets our basic needs; its length is walkable and served by regular daily buses and has painted bike lanes. It is an ideal candidate for the 15-minute neighborhood we have codified in our new Official Plan.

And some zoning provisions work against the goals we set for our city. In the TM zone there is a requirement to set the building back 2m above the fourth floor as well as to respect an angular plane of 45 degrees from the rear setback.

Setting the front of the building back 2m above the fourth floor is intended to maintain a four storey sense of scale at the street line. This is required even if surrounding buildings are taller.

As John Loric writes in Spacing, the idea behind the angular plane setback is that rear walls step back to preserve the privacy of adjacent detached homes and yards, stepping back walls at 45 degrees from an imaginary line 15m above the ground.

These setbacks mean the rear half of a building above the fourth floor becomes marginal or useless: the fifth floor loses about 3m (10ft) of buildable space while the 6th floor loses 6m (20ft) of space. That shrinks fifth floor units from a comfortable 800 sq ft to under 600 on the fifth and as small as 370 on the sixth. Meanwhile, the street-facing fifth and sixth floor units shrink from 800 to 650 sq ft.

Smaller units might become more affordable but reduce the opportunity to house families. Adrian Crook, the Vancouver blogger and dad, is raising 5 kids in an apartment, but its 1,000 sq ft. If we want places for families, we need to have family sized apartments.

Each of the setbacks further complicates roofing, structural, plumbing and heating systems, increasing costs and making the homes more expensive.

Planning guidelines ask that the front of the building be broken up to reduce the visual impact of a building and “create visual interest.” As Lori Drost, Berkeley’s Vice Mayor noted in an epic thread, this further decreases building energy efficiency.

Restricting development on Minor Corridors implies the City is choosing to prioritize avoiding conflict with existing residents over housing affordability. Maintaining an angular plane setback, combined with other planning restrictions, chooses to prioritize the possible privacy of a few residents over the needs of the many new residents who deserve a place to live in thriving walkable communities.

This article was also published in the Ottawa Citizen.

Toon Dreessen is president of Ottawa-based Architects DCA and past-president of the Ontario Association of Architects. For a sample of our projects, check out our portfolio here. Follow us @ArchitectsDCA on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram.