How can Ottawa decrease its tolerance for crap?

Ottawa, as a city, relies on the federal government and National Capital Commission to do the heavy lifting when it comes to our buildings, parks, and social infrastructure. Imagine Ottawa without the Rideau Canal, national museums, the Experimental Farm, and Ottawa River parkways and pavilions.

Take those away, and our city can seem an uninspiring place.

When the Globe and Mail listed the best architecture to visit in Ottawa, not a single municipal place or building made the list. The City of Ottawa has never won a Governor General’s award for architectural excellence and rarely wins prizes for design excellence from the Ontario Association of Architects. There is a blandness that underlies what we build.

Our city shouldn’t be about prizes and awards for the sake of glory.

Our city should be about building better places for people. We need places that enhance our quality of life and create social equity, reflecting our belief in issues like reconciliation, accessibility, and social justice. What we build is a sign of what we value. If the people of Ottawa want inspiring, uplifting, sustainable parks, buildings, transit systems, and social spaces, we need our politicians to know. And they, in turn, need to act.

Dreessen: Despite billions of dollars in investment, lack of design for people results in semi-permanent scaffolding to offer shelter for transit users. Photo © Blazej Marczak www.bmarczak.com used by permission

Consider the LRT. Our lack of concern about actual people using the LRT meant we didn’t get public washrooms at every station; the only reason we have any is that the province insisted on one at either end. Local advocacy secured two additional locations; why does it take public effort to make inclusive places instead of this being an embedded design requirement to create a more equitable city?

Our LRT has very few places to sit and some stations, like Hurdman, needed millions of dollars in temporary scaffolding to provide basic shelter. That scaffolding is now at risk of being removed because we say we can no longer afford the rental.

While the Sussex courtyards (managed by the NCC) are lovely, the rest of the ByWard Market (city responsibility) is in poor condition: an unfunded development plan pins its hopes of renewal on a Public-Private Partnership, the same kind of contract model that brought us the LRT and costs more and delivers mediocre results.

Dreessen: An uninspiring maintenance shed isn’t the worst, but certainly isn’t the best we could do; its mediocrity spoils the surroundings and doesn’t live up to its potential. Photo © Blazej Marczak www.bmarczak.com used by permission

The skating rink at City Hall is a wonderful addition to the public realm. Of course, it needed a shed to store the maintenance equipment. The best we managed was an ugly metal box, slapped on the side of an otherwise beautiful civic building. Compare Ottawa’s maintenance shed to the one in Guelph which graces the backdrop of thousands of Instagram photos as being a well designed, beautiful structure that does double duty by providing a place to sit and put on your skates.

Is the Ottawa maintenance shed the worst thing in the world? No, but it’s hardly the best.

These examples are the product of a system that undervalues the role design plays in creating the city we aspire to be. We need to create a culture of design.

That means creating parks and buildings that people want; that function and meet their needs; that help them improve their lives and live to their best potential. This is social infrastructure.

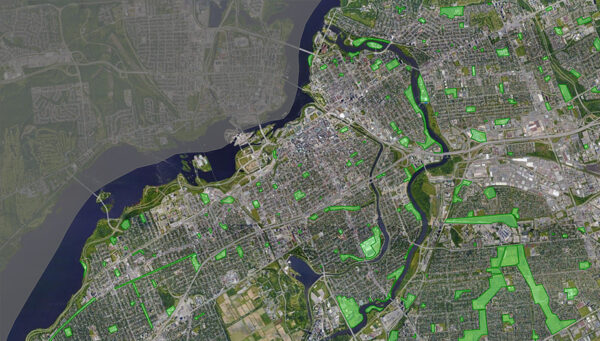

A map of Ottawa with municipal parks highlighted in green (image created by Architects DCA based on Google maps)

What Edmonton won’t accept

We should strive for excellence in what we create. Famously, in 2005, then-mayor of Edmonton Stephen Mandel said, “Our tolerance for crap must be zero.” Since then, Edmonton has been on the forefront of creative, sustainable buildings, parks and public infrastructure, garnering international attention for the quality of work being commissioned.

What is Ottawa’s tolerance for crap?

Adopting a municipal architectural policy would be a good place to start. This guidance already exists in architectural policies from other G7 countries. We should be aspiring to be as graceful, beautiful and sustainable as Berlin, London, Tokyo, or Washington. Aspirational slogans of being “world class” fall apart when we look out the window: we can be “world class” but it takes a design culture to get there.

Setting a policy goal provides a lens through which other decisions can be evaluated and measured. Some goals may exist in policies like the Official Plan but aren’t integrated across other policies or decision making. We might promise to invest in climate change and declare a crisis, but lack of coherent policy may then result in failing to budget accordingly. An architectural policy can help guide decision making.

Brent Toderian, the former Vancouver chief planner, has said, “The truth about a city’s aspirations isn’t found in its vision. It’s found in its budget.” Ottawa chooses to spend more money on roads than housing, libraries, community centres, parks, pools, and washrooms. By contrast, the city of Edmonton chooses to spend hundreds of millions of dollars annually on public parks and buildings. Edmonton is a city with a comparable population where residential property taxes are about the same as Ottawa. It comes down to a matter of choices, guided by policy, and public will for better places.

What we build matters because it’s a reflection of what we value. If our society chooses not to build public washrooms, and doesn’t bother to maintain the buildings we have, we are telling our residents, the world, and future generations, that we’re not serious about lasting value or beauty. The basic human rights are secondary to artificially low taxes and supposed austerity.

Originally posted in Centretown Buzz.