Venice Biennale gets at ideas behind what, why and how we build

Architects in Canada, now is your chance: the deadline for submission is November 29.

Every year Canada is given a rare opportunity to present our best creative talent to the world. Each year are lucky to be one of only 30 permanent pavilions in the Giardini (botanical gardens) of Venice where, in alternate years, we showcase the best of Canadian Art and Architecture. Our pavilion, restored and re-opened to the public in 2018, showcases Art and Architecture, showing the world how Canada confronts creative challenges.

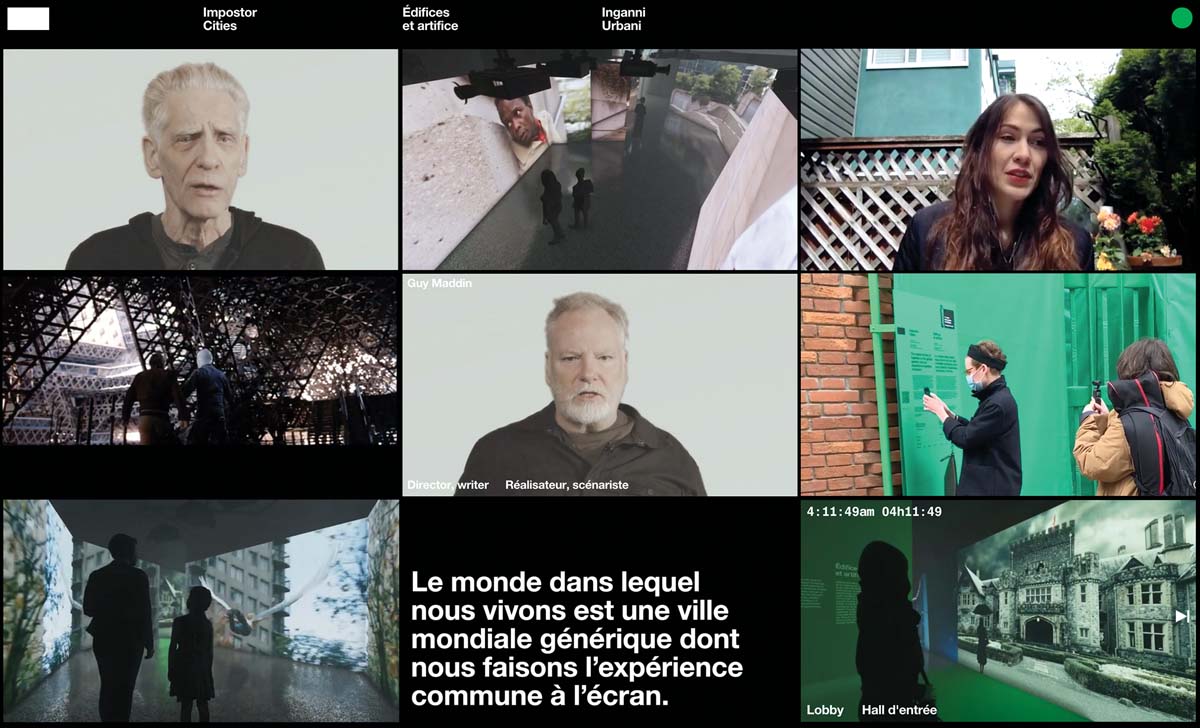

Image: The rich content of the Imposter Cities exhibition—including a chorus of interviews, film clips, and on-site segments—is accessible through its interactive website, at impostercities.com.

Past expositions in Art have included, since 1952, some of Canada’s leading artists. Concurrent annual expositions in music, theatre, film and dance attract thousands of visitors to the Giardini. This is the only international exhibition to which Canada sends official representation. A chance to showcase Canadian talent not only is an opportunity to celebrate the works of the artist on exhibit, but it’s a chance to raise the profile of all Canadian artists. In 2021, the Canadian exposition focused on the idea of how Canadian architecture is “film-famous” as a stand in for other international cities. The exhibition, wrapping the pavilion in green-screen material, proposed new ideas in thinking about what Canadian architectural identity can be. Why do our cities look like other cities? How can we create cultural identity for Canada if we look like everywhere else? Taken further, as we grow our own cities, we can start to question the homogenization of our built environment: should all our places look the same or should homes, offices and stores in Vancouver look different than Toronto, Montreal, Halifax or Yellowknife?

2018 explored the notion of the Unceded land; the relationships between Canada, as a colonial state, and the Indigenous people. 2016 also explored an Indigenous relationship between colonialism, resource extraction, treaty rights and Indigenous people around the world through the lens of mining companies overwhelmingly headquartered in Canada.

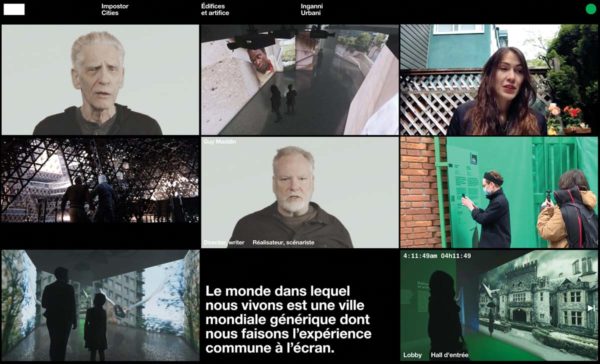

Image: In The Evidence Room, reproductions of a gas-tight hatch, a door with a protected peephole, and a column for lowering gas pellets present architectural evidence for the killing chambers at Auschwitz.

In addition to the official exhibition at the Canadian Pavilion, other exhibitions and ideas are presented. In 2016 the Waterloo School of Architecture presented an exhibit on forensic architecture, looking at the work of Robert Jan van Pelt and how architecture can be used to refute Holocaust denial through the architectural evidence of Auschwitz. This moving, powerful, work was later staged at the Royal Ontario Museum. The Evidence Room was described as “the greatest crime ever committed by architects.”

Image: Arctic Adaptations at the Venice Biennale 2014. Image courtesy Andrew Latreille Photography.

This year, in addition to Imposter Cities, Toronto’s Lateral Office expanded on their 2014 Biennale exhibit on Nunavut to explore domestic life in the eight nations that have land claims in the Arctic. As reported in Canadian Architect, this work examines the challenges of Arctic life, amidst the added challenges of land claims, resource extraction, climate change and politics. In the Arsenale, formerly shipyards and naval bases for the Venetian Navy, Phillip Beasly’s installation examines metaphysical questions of how we live, dwell and die through an interactive exhibit that creates a multi-sensory experience that suggests how architecture transcends national borders to interact with nature in creative ways that allow built form to respond to its environment. This is an exciting development in Beasley’s work as he continues work initially exhibited at the Biennale in 2010.

These works are important because of architecture’s importance. This goes beyond pragmatic questions of building codes, standards, energy efficiency and building permits to consider the broader meaning of built form.

The architecture we build, and how we do it, affects our mental and physical health; it affects our economy, our climate change goals and our quality of life.

But beyond the practicalities of everyday projects that we design, build and occupy, exhibitions like the Venice Biennale create a forum for discussion on the ideas behind what we build, how and why. The Biennale challenges exhibiting countries to propose architectural solutions to societal and technological issues.

On October 14, 2021, the Canada Council for the Arts announced the call for expressions of interest. Ideas must be bold; they must “inspire, challenge and respond to current realities.”

According to Carol Warren, program officer for the Canada Council for the Arts, “The Venice Architecture Biennale is an important, prestigious international showcase for the creativity and inventiveness of Canadian architecture and its new approaches to the built world that engage with many challenges of our current times including environmental sustainability, accessibility and freedom and diversity of cultural expression.” It is this spirit of creative, multi-disciplinary, inventiveness that drives architects every day.

The theme of the exhibition won’t be announced until next year, but we can guess that themes of climate change and sustainability will be prevalent. It’s also likely that themes may centre around how the world has, or has not, changed because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Canada, when compared to other liberal democracies, fared better than many countries in deaths per million, but when looking at deaths in long term care, we fared far worse. Architectural solutions to consider how future pandemics, and deaths, can be avoided, may become a theme in 2023.

Themes of housing, Indigenous and treaty rights and dispossession of traditional land uses are issues that we confront in Canada on a regular basis. But we are not unique in this; similar themes may explore decolonization across the world.

The carbon cost of creating buildings; the challenges of accessibility and aging in place and the challenges of rising sea levels are all issues that confront many countries.

In short, there is no shortage of possible themes. The biennale organizers have a tough series of choices ahead, from selecting the theme to appointing a curator who will champion an idea to challenge the profession and the world.

The Canadian jury of four leading champions of Canadian architecture will similarly have to make a difficult choice. Aside from artistic merit, a potential exhibition must demonstrate an ability to capture the attention of a wide range of visitors and spark a stimulating conversation about Canadian architecture both domestically and abroad. Ultimately, the exhibition must also be feasible; it has to be presented and staffed for 6 months.

This is an expensive and logistical challenge. An exhibit must be planned that engages the public, contains both physical exhibition components, but can also be livestreamed, downloadable or contain virtual elements, interactive exhibit components and, of course, has to have personnel available to live and work in Venice for the duration of the exhibit. With hundreds of thousands of visitors, this requires dedicated, knowledgeable, staff combined with a coherent and easily presented package of information that can engage visitors from around the world.

Sponsorship is essential to provide the supported needed for a quality exhibit that shows Canada in the best possible light. That is why I am joining the list of sponsors to support Canada’s role on a world stage.

Canada’s architectural community needs to become more engaged. We need to seize this opportunity to showcase not just our creative talents in creating iconic, well loved, sustainable architecture, but to show how Canada can respond to the pressing issues of our time.

The Canadian public needs to be aware of the powerful role architecture can play in their lives. The 1951 Massey Report, “widely considered to be the important document in the history of Canadian cultural policy,” also noted that the Canadian public is too little aware of the power of the architect to enliven and enrich their lives. In the 70 years since the Massey Report was published, little advance has been made to make architecture more relevant to Canadians.

As an architect and as a Canadian, I am immensely proud of the work Canada has presented in Venice. I had the honor of attending the grand openings in 2016 and 2018, on behalf of the Ontario Association of Architects, a sponsor both years. Celebrating, and honoring, the work of Canadians in an international setting is a humbling and educational experience. That is why I am joining the list of sponsors to support Canada’s role on a world stage.

Architects in Canada, now is your chance; the deadline for submission is November 29 2021.

Canadians interested in architecture, now is your chance: help make Canada’s architectural voice stronger by supporting an architect and showing that architecture matters.

TO DONATE:

This article was also published in Canadian Architect.

Toon Dreessen is president of Ottawa-based Architects DCA and past-president of the Ontario Association of Architects. For a sample of our projects, check out our portfolio here. Follow us @ArchitectsDCA on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram.